Alfred H. Barr’s diagram is a visual device based on a spatial ordering logic. In other words, the decoding and interpretation of its potential meanings comes from a specific arrangement of the elements on the two-dimensional level, in addition to aspects related to its graphic and ortho-typographic configuration. It is significant, for example, that the top-down reading required by the diagram’s design (with its timelines framing the space laterally on both sides, the direction of the arrowheads and the rectangular format itself) has been key to its overall interpretation in genealogical terms, despite the fact that Barr’s diagram is much more than genealogy, as it includes a whole set of transversal relationships that connect the different movements, styles and artists included in it.

The exhibition Genealogies of Art (2020), which inspired the Barr X Inception CNN experiment, explores precisely these transversal relationships in Barr’s chart, despite the fact that its title focuses to the genealogical matter. Thus, in a risky exercise of great creativity, the museum exhibition transforms the two-dimensional diagrammatic scheme into a three-dimensional, physical space, modelled by the visual relations that the physically present art pieces establish with each other.

In this way, Barr’s diagrammatic abstraction, with its indexical function, is embodied in a three-dimensional artifact with a spatiality which is different from the two-dimensional one; a spatiality in which the visual-formal connections prefigured in the diagram are visually present, and they also create other levels of relationship that had not been drawn by Barr, but that are made possible by the co-appearance of images in the same space, as Aby Warburg (1866-1929) knew too well.

Genealogies of Art is a space that can be, not only visually, but also physically travelled and experienced by the visitor, in a process through which the Euclidean physical space becomes a duration [1]; a space that unfolds as the tour progresses, as we move from one room to another; in short, we seem to be in a three-dimensional version of Warburg’s panels where the intervals or interstitial spaces between images have been completely transformed into space-time.

The Barr X Inception CNN project aims at contributing to these spatial readings by proposing another type of spatiality.

Among the profound transformations that have taken place in our current technologically mediated society, perhaps the one that most affects the very configuration of the field of art is the metamorphosis that the ontological dimension of cultural objects has been experiencing for some centuries now. In the same way that, thanks to the advances in photography and mechanical reproduction tools, the 20th century completed the process started by the graphic media in which cultural artefacts were transformed into their corresponding visual productions, the spread of digital technology in the 21st century has brought about the transformation of these works into a mass of information in the form of bits and pixels, i.e. numerical values that can be mathematically computed.

This ontological change is far-reaching as it implies, first of all, that the visual-formal characteristics that we identified as belonging to digital images are nothing more than numerical data that are recreated before our own eyes on a screen. It is important to emphasize this issue because the image reconstruction in the digital device often generates the optical illusion of dealing with images as iconic entities, when, in fact, they are items of digital information. Secondly, and as a consequence of the above, this ontological transformation also implies that the analysis (and ordering) of cultural objects that have been transformed into digital reproductions turns into a mathematical problem. From a computational point of view, the digital image is nothing more than a surface of numerical information from which information of a numerical nature can be extracted.

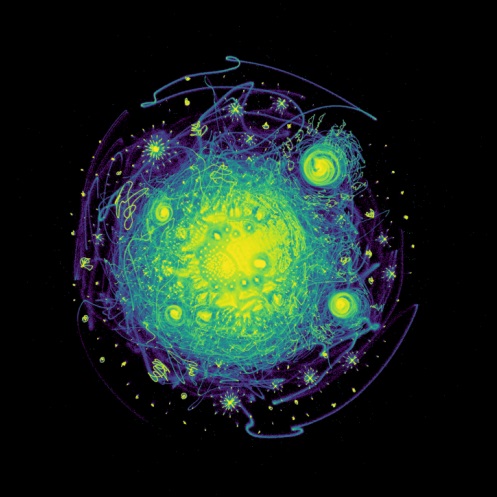

This is the scenario where artificial neural networks -computer architectures linked to Artificial Intelligence (AI)- operate. In particular, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) are computer vision devices trained to detect formal similarities between digital images transformed into vectors of numerical information. Its projection in the two-dimensional space, which in this project has been named “visual field”, responds to these criteria of contiguity, so that the greater or lesser proximity between the images must be interpreted as an indication of their greater or lesser visual-formal similarity. However, what is this visual field made of? What is its nature?

At first sight, the machine produces a visual display which sets in motion a relational conception of the images distributed in space according to a certain morphology. Thus, this type of visual device should and must be placed in a material and historical continuity in relation to other devices that, over time, have formed the way we look at cultural objects and, therefore, interpret them in their iconic-iconographic dimension. It is impossible not to think of Aby Warburg’s Atlas Mnemosyne (1926-1929), which is also the result of a relational view of images[2]. There are, however, substantive differences that lead us to speak of a new type of spatiality. Barr X Inception CNN presents the work of unsupervised computer vision technologies, that is, technologies that classify, categorise and order images with strictly computational processes, without direct intervention of humans and which are, therefore, independent from the epistemological categories that make up the disciplinary knowledge of Art History. Since computer vision is the calculation of numerical information, it is mathematical logic that lies at the basis of the possible production of meaning: in other words, the computer establishes more or fewer similarities between numerical data , bringing digital images – transformed, let us not forget, into vectors of numerical information – closer or further in a vectorial metric space.

Consequently, and this is obvious, in the space produced by an Inception CNN the cognitive-psychic function of a human being is replaced by calculation and computation. Mathematical logic thus replaces perceptive action as a cognitive act, the action of thinking as a connection and semantic association of ideas, and the psychic action of memory, be it conscious or unconscious. The visual and semantic connections based on perceptive-cognitive abilities and on the memory function are replaced by the mathematical computation of visual-formal characteristics translated into numerical data.

Therefore, and unlike the diagrammatic configurations that have followed one another throughout the History of Art, the morphological configuration that we are now dealing with does not represent a pre-existing idea in a human mind, a formulated thought or a previously articulated story; it is not the construction of a visual story wanting to tell something or reveal a psychic, conscious or unconscious state. On the contrary, it is nothing more – but nothing less – than a computer creation translated into a-ideas or a-psychic forms, if we can use these terms to describe these visual structures that do not represent or convey ideas, thoughts or stories that have previously inhabited a human mind; nor are they the result of specific mental states. The formal configurations resulting from the computational processing are not, therefore, representational forms, but rather forms of a machine action and the product of its rationale.

Here, the concept of knowledge generator formulated by Johanna Drucker [3] can be used to explain these configurations as generative forms, that is, forms generated by a machine with a different rationale from the human’s one, but that operate – for that very reason – as spaces not “of” but “for” the production of knowledge. Formal configurations, therefore, that lead to the discovery of the information provided by mathematically computed visual data that must be subsequently spun into a story, be it a narrative or an account, that gives it meaning. Forms that invite creative exploration rather than a decoding reading; in short, visual forms that need an interpretation that does not come from the hermeneutic task – since there are no underlying ideas to discern – but from an exercise in creative heuristics. This is how these configurations become meaningful to humans, and this is how they are instated in spaces of negotiation between the quantitative saying and the qualitative conception. That is why, in my opinion, these generative visual devices constitute the interstitial space between the machine and the person. This space of computational nature, made up of mathematically processed information, acts as an interface between the rationale of the machine and that of the human being; the medium in which the machine product becomes intelligible to people by giving it a meaning.

As vector space, the visual field produced by an Inception CNN is, in reality, a field of forces made up of images that, in their role as vectors of numerical information, act as lines of force with a determined direction and intensity. The visual shape that can be observed in the vector space expresses therefore a given “state”, the result of the tension established between the images-vectors-forces when they reach a point of equilibrium. The constellation or visual field is therefore the result of all the forces acting at the same time, which will be destabilized and/or reconfigured as soon as an image-force-vector moves, or new forces-vectors are incorporated. The image, as a point in a space, is not only it, it is also the set of forces in which it is placed. The state of equilibrium is, therefore, a transitory permanence, the state between a multiplicity of possible displacements and reconfigurations. The field of vision is thus intrinsically dynamic.

The vector space also gives shape to the structure and morphology that comes from a space built from connections and contiguity between cultural objects of a visual (formal) nature. What becomes visible is the form and structure behind the data, revealing continuities and discontinuities, connections, overlaps and distances. In this type of organization of the visual field, the possible interpretation derives from the morphology and topology resulting from the position and distribution of elements in a given space, from the spatial structures that they form, from the distance relations that these elements establish between themselves, from the force-actions exerted by the images converted into mathematical vectors. Hence, the arrangement of the cultural visual production becomes a problem of spatial distributions, topological structures and morphological reconfigurations. As Warburg warned, when thinking topologically – and not typologically – the field of visual forms eludes approaches that tend towards dichotomization, binarization or simple comparison, thus adding complexity.

Therefore, this model of reorganization of the cultural visual production provides interesting material when proposing alternatives to the chronotropic axis of traditional computer systems: This extends the possibilities of an intellectual debate established long ago in historical-artistic thinking, which already mentioned trans chronology (Warburg), anachronism (Didi-Humberman, Kubler) or heterochrony (Moxey). As such, the topological space is also a space-time, which integrates the spatial dimension -points in space- and the temporal dimension -vectors-force. As stated by Graciela Speranza, “topological time expands, contracts, folds, curls, accelerates, stops, and links other times and other spaces”[4].

These morphological and topological configurations also question the traditional geographical and geopolitical delimitation categories that form the basis of the national model of art history, which has, admittedly, already been widely discussed. However they are equally essential to the no longer so new paradigm of transnational and/or global art history, For, although the latter is proposed as an overcoming of the national model, here too the historical-artistic phenomena are referred to geographical and geopolitical coordinates, given that it is their location -related to a border- that gives them entity as global or transnational phenomena. In a graph or in a topological space there are no geopolitical or geographical borders; what we find is a spatial continuum made of connections or degrees of proximity and/or distance, tensions in a field of forces. All this prompts us to explore the transformation of spatial narratives into topological narratives.

Moreover, this space is also a graded (scalar) one, because the location of the elements is not given by fixed attributes that are part of the invariable ontological nature of cultural artifacts, but by degree values: the distance between the images does not refer to an ontological-typological difference, but to degrees of greater or lesser similarity.

It is, ultimately, a high-dimensional space. The place where digital images live, inasmuch as they are diverse and multivariable data sets, constitutes an informational space shaped by the recombination of multiple characteristics (features) that are articulated in a huge number of possible dimensions (feature space). That is why it is referred to as high dimensional, n-dimensional, or hyper space. Each image -as a visual object- is a point in that high dimensional space. Although it is true that dimensional reduction algorithms, like those used in this project, are designed to generate a low-dimensional representation in order help the human mind (which is used to see in three dimensions) understand an extensive number of characteristics and dimensions, what is actually represented here is multidimensional information. The exploration of the implications that this type of multidimensional and vectorial space may have for cultural interpretation and analysis, is still at an early stage [5]. However, it seems clear that the exploration of its potential as an alternative space to the notion of physical-Euclidean space and geographic space, is of great interest. This is because it opens up a line of research that can tackle, from a topological, physical and geometric approach, the problem of how to order complex n-dimensional phenomena, which are projected into multiple possibilities, are transformed into gradual scales and which, therefore, cannot be catalogued, categorised or classified according to classical logic, with its inexorable delimiting function. This conflict between the irreducibility of complex cultural phenomena to be classified in watertight categories and the need to establish an order that allows us to grasp their complexity has been an intellectual concern of Art History and of cultural and visual studies in general, which can now be tackled with new instruments of exploration and thought.

* Some of the ideas presented here are taken from: Rodriguez Ortega, Nuria. “Artefactos, maquinarias y tecnologías ordenadoras. A propósito de los catálogos de arte», en Catálogos desencadenados. Málaga: Vicerrectorado de Cultura-Universidad de Málaga (in press), where this subject is further developed.

Recommended quotation: Rodríguez Ortega, Nuria. Other Spacialities Brief Comments», en Barr X Inception CNN (dir. Nuria Rodríguez Ortega, 2020). Available on: http://barrxcnn.hdplus.es/espacialidades-otras/ [date of access].

[1] Carlos Miranda has a lot to say about this.

[2]Differences and similarities between the vector space produced by a CNN and the Warburg panels are analysed in more detail in Rodríguez Ortega, Nuria. “Artefactos, maquinarias y tecnologías ordenadoras. A propósito de los catálogos de arte», en Catálogos desencadenados. Málaga: Vicerrectorado de Cultura-Universidad de Málaga (in press).

[3] See DRUCKER, Johanna. Graphesis. Visual Forms and Knowledge Production. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 65.

[4] ESPERANZA, Graciela. Cronografías. Arte y ficciones de un tiempo sin tiempo. Madrid: Anagrama, 2017.

[5] In fact, considering dimensionality reduction strategies, other alternatives are also being put forward, for example, SANDERSON, G. Thinking visually about higher dimensions. Available on: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zwAD6dRSVyl [date of access: 18-3-2020], that make a distinction between seeing and thinking visually. This opens up another interesting avenue of exploration.