The visual field resulting from the computational analysis is made up of 21 clusters grouping the X artworks that form the dataset. These clusters are located in a vector space based on a distribution algorithm that brings together the most similar images and moves the most dissimilar ones away from a visual (formal) point of view. Thus, the spatial structure of the visual field, the distribution of clusters, the internal configuration of each of them and the distances between the images are essential for their interpretation.

The reading below is presented in comparative terms, with the aim of outlining the differences and similarities of the genealogical and relational proposal raised by Alfred H. Barr (1902-1981) in his diagram (1936). Although in both cases the operating principles are apparently similar, given that an Inception CNN detects visual (formal) similarities between images, and Alfred Barr’s intellectual approach advocates an evolution of artistic-visual production in formalist terms, all intellectual development – as we well know – implies a construction where layers of theoretical, epistemological, cultural and disciplinary modelling are intertwined, affecting and modulating the interpretation resulting from the verification of formal “evidence”. As already mentioned elsewhere, the idea of the teleological becoming that is behind Barr’s diagrammatic configuration is already in itself an intellectual positioning that exceeds the simple observation of the forms objectively present in the works analysed.

In fact, one of the first, very obvious differences resulting from the observation of the visual field is the rupture of linearity in favour of a complex system of transversal and multi directional relations.This idea is at the base of the reinterpretation that the exhibition Inventing Abstraction (MoMA, 2012) makes of Barr’s diagram, as the genealogical progression of the diagram is transformed into a network configured by the connections established between the artists who contributed to the development of abstraction as a plastic art proposal. From the point of view of the visual field, which is the topic we are covering, we think that this configuration better expresses the idea that formal relations are multiple, non-linear and not necessarily progressive. Thus, the genealogical and teleological narrative is deactivated in this organizational model.

It is true that Barr’s diagram is also based on a relational conception of the artistic-visual productions of the first decades of the 20th century. Thus, if we take off the timeline that frames the diagram on both sides, what we are left with is a graph of relationships between specific authors styles and movements. However, the visual power of these timelines and the indexical nature of the arrows, directing the eye, explain very well the interpretation in terms of the linear genealogical evolution that has prevailed in the readings that have been made to date. The comparison between both visual artefacts (diagram and visual field) helps to show how the formal structures mentioned by Barr and later Clement Greenberg are the product of an ideological interpretation, of a way of understanding the evolution of visual culture in the field of art, rather than the result of the scrupulous verification of a theoretical objective formality.

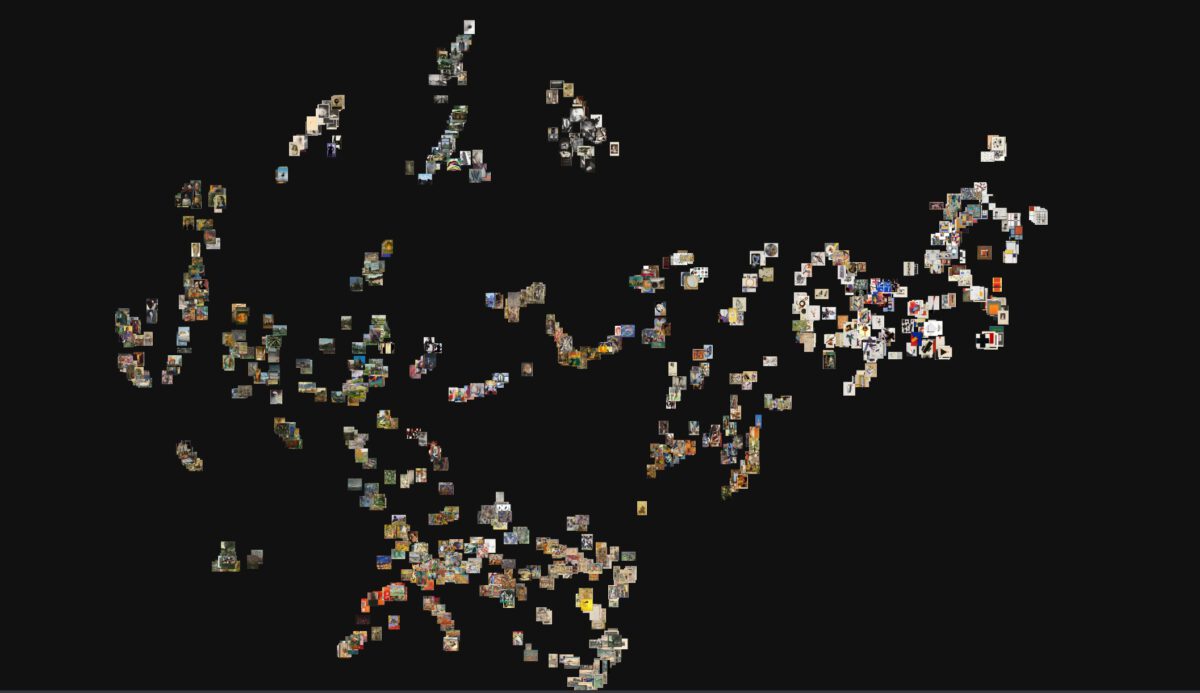

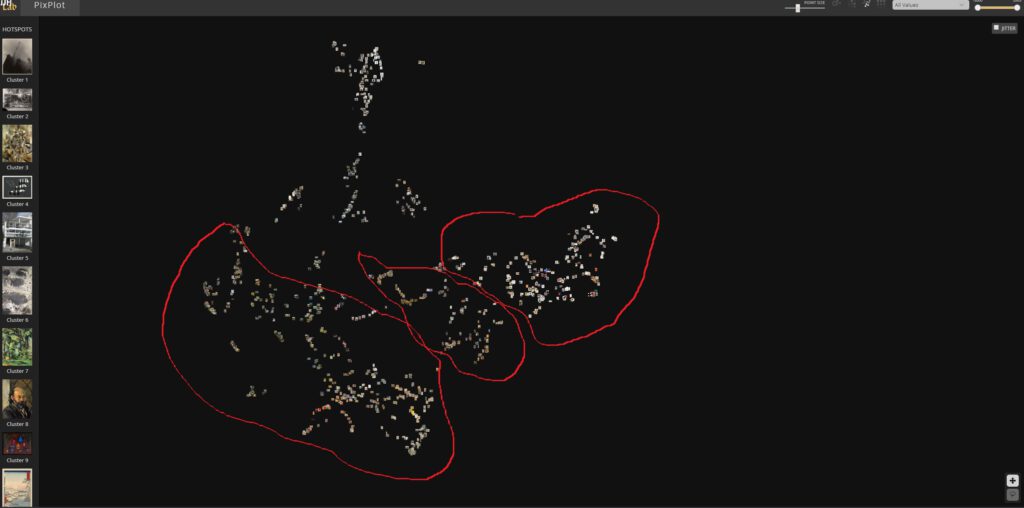

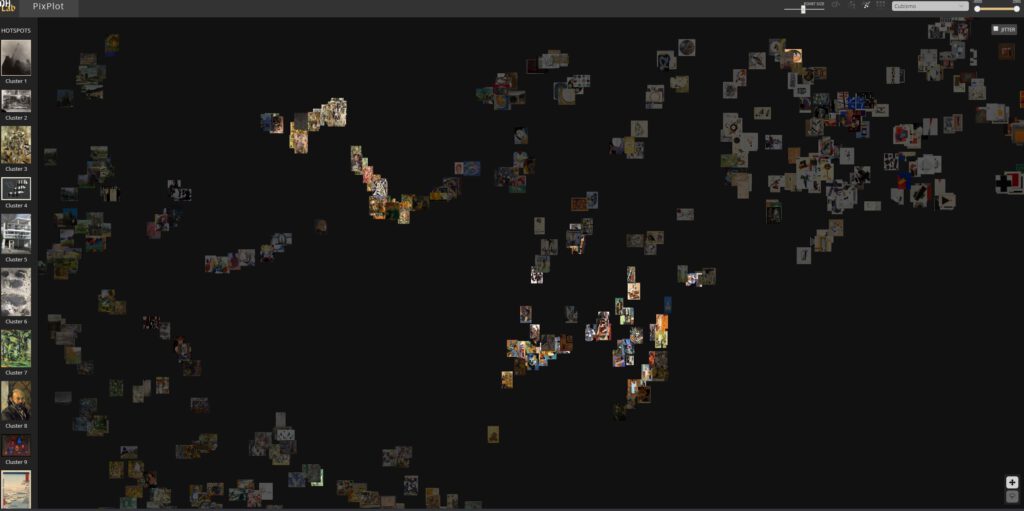

A second very clear difference is the disappearance of the categories of disciplinary classification in the organisation and arrangement of the artistic and visual production. As opposed to Barr’s nodes, which abstractly summarize the artistic-visual production in large groups previously established by the theoretical-critical and historiographic instances, the visual field proposes an organization in clusters that are formed exclusively by the Inception CNN’s operating logic . Thus, the cluster replaces the ism, the movement, the style, the artist, as a category of analysis and reading parameter. This is no trivial fact as it implies that the artworks (their digital reproductions) appear distributed in the visual field according to their visual (formal) similarities, mathematically computed, regardless of which stylistic-formal category they follow as per the traditional Art History classification system, which still operates on an epistemological level. As a result, this organizational model makes the configuration of the artistic iconography more complex as it emphasises the processes of visual interrelationship that go beyond classificatory schemes, enabling unprecedented interconnections between works that Art History tends to locate in different places of its epistemological system. Thus, the monolithic elements of Barr’s diagram (Dadaism, surrealism, fauvism, etc.) are, in some cases, disseminated throughout the visual field, leaving the works disintegrated in different clusters and in places distant from the visual field (Fig. 1).

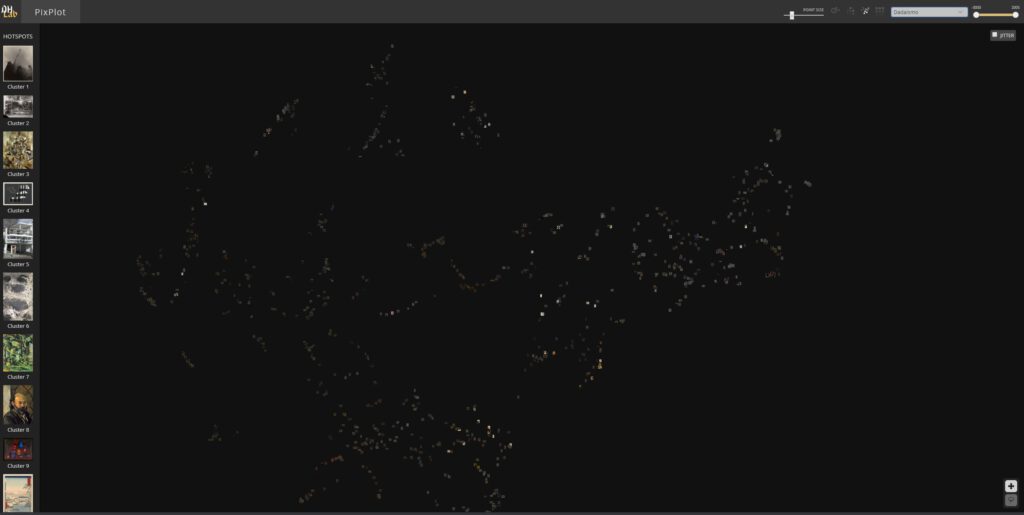

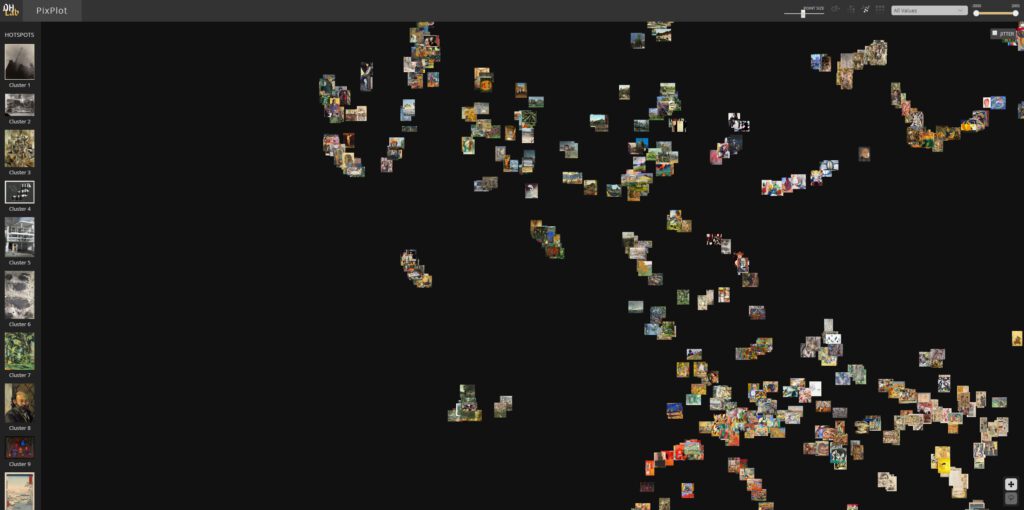

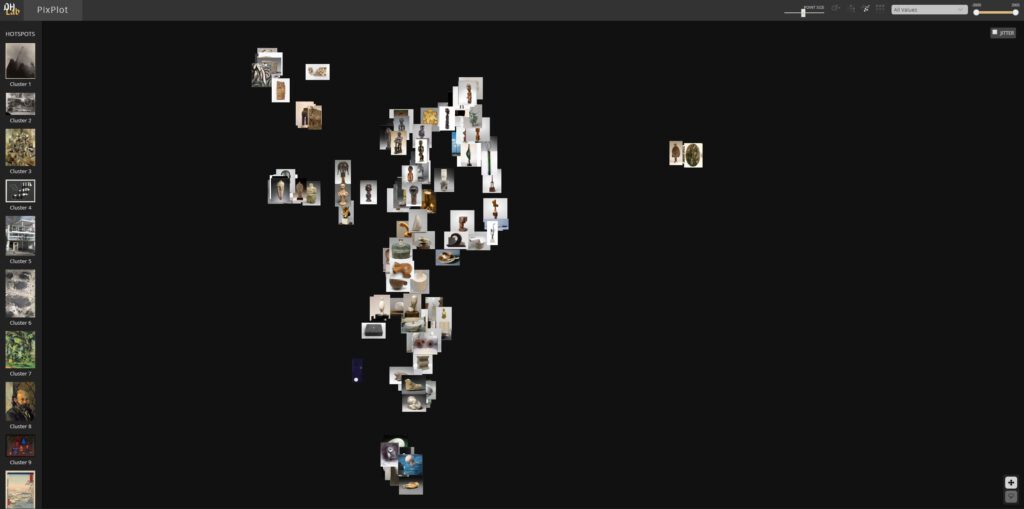

This dissemination helps highlight the formal heterogeneity that characterizes some of these movements, isms or styles, and provides materials to analyse visual relations in terms of open and multidirectional relationships. By contrast, those clusters whose configuration coincides with the previously established isms or styles acquire special relevance, as is the case with cubism -which we will discuss below- or Japanese Prints (cluster 10). This cluster, for example, is practically isolated in a peripheral place of the visual field, standing out for the homogeneity of its plastic values, at the same time extraordinarily different from those of the rest of the artistic displays (Fig. 2).

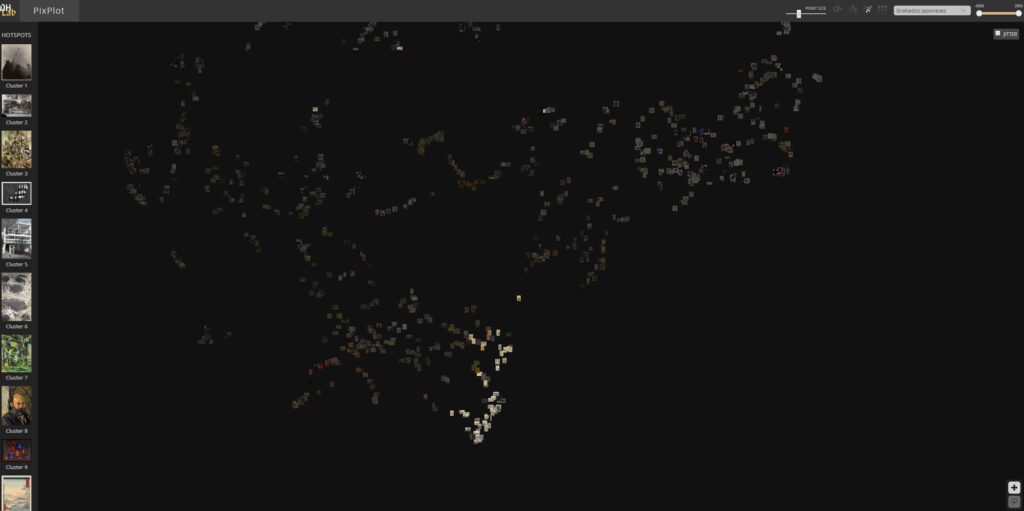

All this emphasizes the trans chronological character of the images, of the forms and the visual contents, in a kind of computational updating of the Atlas Mnemosyne (1926-1929) by Aby de Warburg (1866-1929). Thus, the proximity between some of the works of surrealism and the production of Gauguin, Cezanne and Rousseau (situated on the left side of the visual field), authors who in Barr’s diagram are situated at the opposite end of surrealism, highlights the advantages of the image visualisation field as opposed to the diagrammatic format when it comes to graphically presenting direct relationships between artistic movements that are very distant in time (Fig. 3).

Nevertheless, and notwithstanding the need to carry out a more detailed analysis of the configuration of each of the clusters and the distribution of the works represented in the vector space, the general morphology of the visual field does not differ too much from the approach behind Barr’s diagram. Let us have a look.

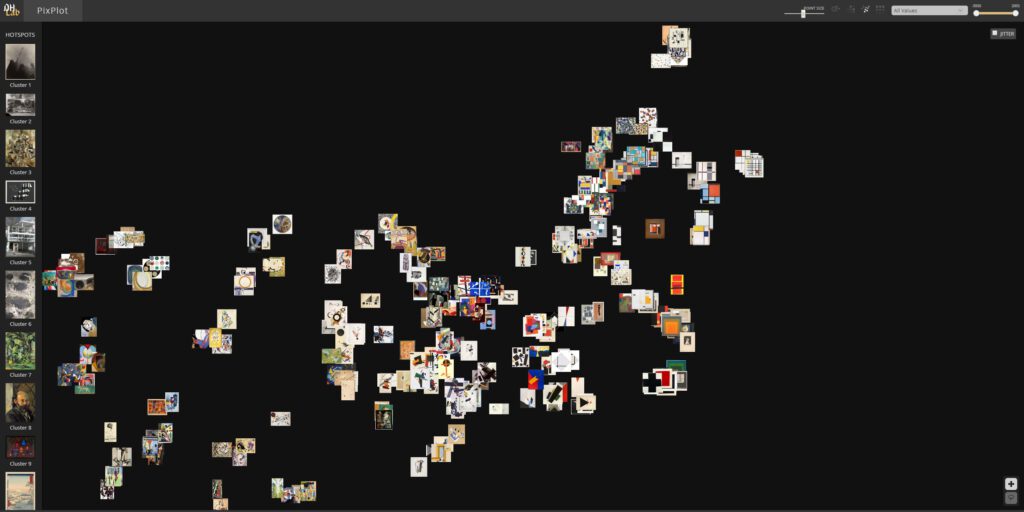

First of all, we can see that the visual field is organized around two large constellations that are located to the left and right of another central set of images (Fig. 4).

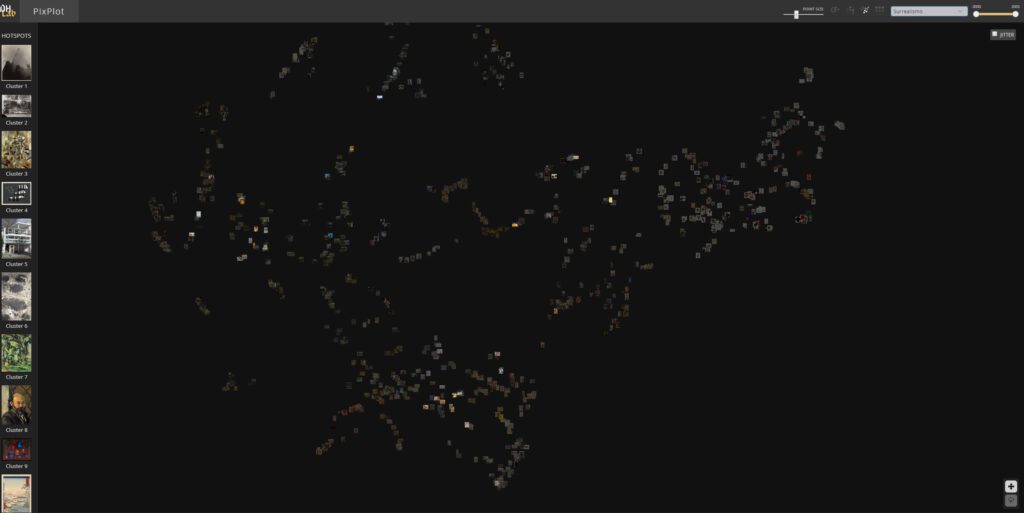

The constellation located in the right area of the visual field includes works that are characterized by their marked geometric forms (cluster 4) (Fig. 5). Most of the suprematist and neoplasticist works are located here. These movements appear as clearly visible entities since their works are placed in groups of images close to one another. However, the works of constructivism and those of geometric abstract art are more scattered throughout this vector space area. As a whole, this group is roughly equivalent to the one represented on the right side of Barr’s diagram, where suprematism, constructivism and neoplasticism converge under the heading “geometric abstract art”. The computer system, guided by visual (formal) values, recognizes, as does the diagram, this tendency towards geometric abstraction.

The second constellation, located on the left side of the map, includes both figurative and non-figurative works, of organic or non-geometric forms (Fig. 6). This constellation can be subdivided into two groupings: a more figurative one (Gauguin, Cezanne, and most of Rousseau) and a less figurative-expressionist one (fauvism, abstract expressionism, non-geometric or lyrical abstraction). Therefore, in a way, this visual cluster could be related to the right side of Barr’s diagram, where the movements that (according to Barr) will lead to non-geometric abstraction are located. However, there are also substantive differences. For example, most of the works of surrealism are scattered among both groups (Fig. 3). One part of surrealist production is close to the areas dominated by abstract expressionism and non-geometric abstract art (lyrical abstraction, Kandinsky); the other is located in an intermediate zone, between the production of Gauguin, Cezanne and Rousseau – as mentioned above. The visual (formal) characteristics of the surrealist pictorial corpus are extremely diverse; the only way they could be connected is by tensioning the plastic form between the abstraction and the figuration poles. The distribution in the visual field clearly exposes this phenomenon, which is identified in the diagram, but is oversimplified.

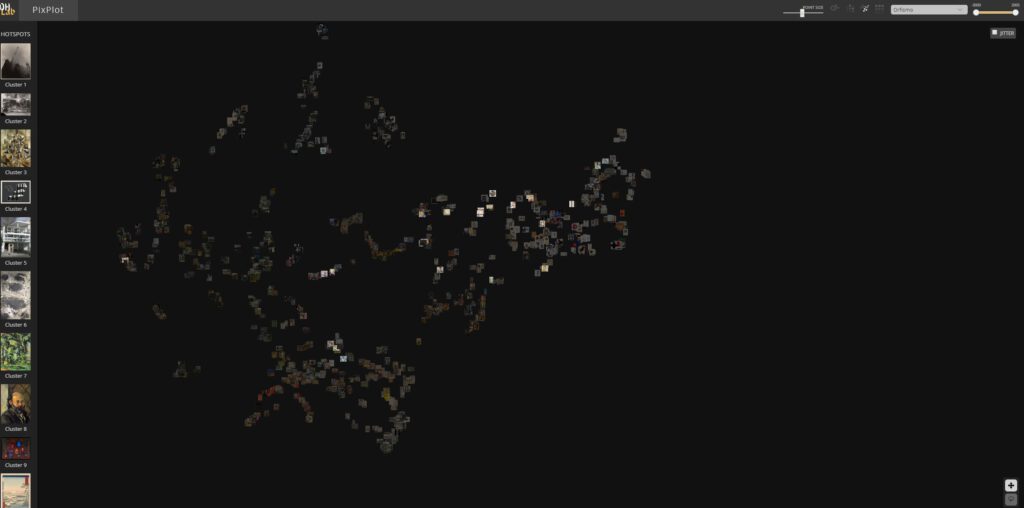

The location of Orphism also differs from its representation in Barr’s diagram. The diagram considers Orphism an experience derived from cubism without establishing any other subsequent relationship (Orphism emerges from cubism and has no further development). The field of visualization poses a different scenario, which complicates the interpretation of this plastic proposal (Fig. 7). Thus, Orphist works are scattered throughout the visual field, approaching the constellation of geometric art, non-geometric art and the central cluster, which is discuss below. For a movement like Orphism, which swings between figuration and abstraction, between the organic and the geometric, this “other” position seems to make more sense than the isolation reflected in Barr’s diagram.

The grouping of images located in the intermediate space between the left and right constellations is mainly made up of cubist pieces (fig. 8). Cubism is divided into two clusters (3 and 14), which seem to correspond to the traditional classification between analytical and synthetic cubism. Despite this separation, these works remain closely related in each of the clusters, and the clusters are also close together in the vector space. This situation and distribution of cubism in the visual field is interesting because, although the precise system of relations established in Barr’s diagram is lost, cubism appears as the most autonomous, homogeneous and, therefore, outstanding entity, located, moreover, in a central space of intermediation. This last aspect was indeed taken into account by Alfred Barr, when he gave cubism the largest typography within the diagram and a place in its epigraph – Cubism and Abstract Art.

Alongside these three image constellations, there is a fourth one in the upper part of the visual field comprising the sculptures included in the dataset (Fig. 9). Brancusi’s sculptures, “Negro sculptures” and “Near-Eastern Art”, all with relatively similar visual (formal) features, are grouped in cluster 20. The grouping of the sculptural works in the same cluster may be due to the very logic of operation of Inception CNN, which tends to group the images it recognizes as three-dimensional shapes. In this respect, in the visual field, African and Oriental sculptures no longer function as Alfred Barr had intended, that is, as catalysts of cubism, fauvism and German expressionism. This result is logical, either because of the way Inception CNN works or because of the creative logics of some artistic movements: they assimilate the forms of “non-Western” sculpture through a complex process of hybridization and synthesis -especially cubism-, thus generating new plastic values that are not strictly equivalent to those of the works they are influenced by. There is, however, a relationship between the “non-Western” and Brancusi’ssculpture that, surprisingly, did not appear in Barr’s diagram. According to Cubism and Abstract Art the work of the Romanian artist was directly influenced by the “Machine Esthetic”. However, in the image visual field it is possible to identify an obvious connection between Brancusi’s sculpture and the “non-Western” one. The equivalences of organic values between both entities make this a more plausible relationship than the one established with the functional-rationalist “machinism” based on refined geometric forms. In fact, the link Brancusi-“non-Western art” has been highlighted by the latest exhibitions and studies dedicated to the artist.

Research and Development Team (R&D Team)

Recommended quotation: EDI. “Interpretation #1 Brief Comments», in Barr X Inception CNN (dir. Nuria Rodríguez Ortega, 2020). Available on: http://barrxcnn.hdplus.es/en/interpretacion-1-2/ [date of access]